Decode your Injury - Return to Sport Stronger than Ever

Have you ever heard a Physiotherapist, or had an MRI that has said you have suffered a Grade 3c Proximal Intratendinous Bicep Femoris Tear that is greater than 5cm?

Have you left an appointment feeling more confused than helped?

This blog is going to break down how to classify your injury so you can understand your body, be more informed and return to sport in the safest and time efficient way to reduce the risk of injury recurrence.

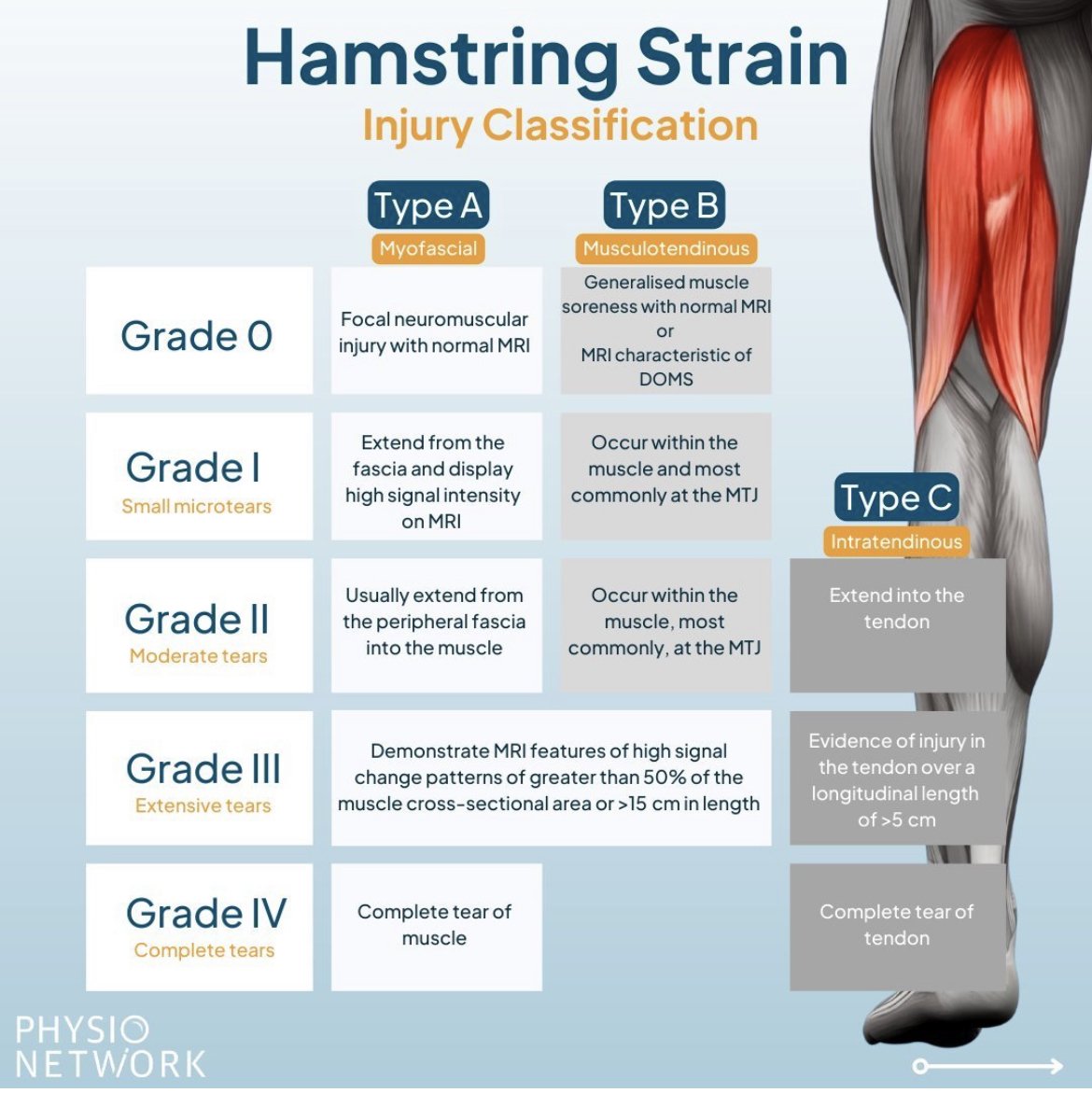

This blog will be focusing on hamstring muscle injuries. Here at Carlingford Active Health, we use the British Athletics Muscle Injury Classification. This system is a research-based method to classify such injuries and uses MRI to support these terms and diagnoses.

General Terms:

This blog will be packed full of big terms so refer here for any help you may need.

The phrase ‘muscle injury’ is a suitable global term that covers all acute grade 0–4 injuries. A Grade 0 injury is considered minor, whereas a Grade 4 injury is a more significant and major injury. Furthermore, it is consensus to use the phrase ‘tear’ to describe all Grade 1–4 muscle injuries (1). We will unpack this all further into the blog.

Also, it is important to note the letter attached to the grade number refers to the anatomical site of the injury; or simply put the location of the injury. They are as follows:

The grading of ‘A’ refers to a myofascial (peripheral aspects of muscle) injury

The grading of ‘B’ refers to a musculo-tendinous (muscle belly) injury.

The grading of ‘C’ refers to an intratendinous (within the tendon) injury.

Grade 0:

What could a Grade 0 possibly mean? A fake injury?

Well not so, Grade 0 injuries are presentations of pain or acute muscle soreness with no structural change’s observable by MRI.

A Grade 0a Injury classifies muscle soreness after or during exercise. There is associated with awareness on muscle contraction. There is little to no reduction in strength when tested (1).

A Grade 0b Injury represents generalised muscle soreness, which most commonly occurs after exercise. Typically, eccentric (lengthening of a muscle) exercises are more difficult and produce this generalised soreness (1).

Grade 1:

Grade 1 injuries is a small tear to the muscle. The athlete will usually have pain during or after activity. The athlete’s range of motion 24 hours after the injury should remain normal. Although, there may be pain on the contraction of the muscle. Strength may be not diminished on examination (1).

There are no grade 1 injuries which involve disruption within the tendon. Therefore, a Grade 1C injury is impossible.

Grade 2:

Grade 2 injuries is a moderate tear to the muscle. The athlete will have pain that will require them to stop activity and inhibit them to continue. The athlete’s range of motion 24 hours after the injury typically will be reduced. It is likely for pain on the contraction of the muscle and a loss of muscle strength with examination (1).

A Grade 2c injury is possible and will extend into the tendon but will be of a size less than 5 cm (1).

Grade 3:

Grade 3 injuries are extensive tears to the muscle. The athlete will demonstrate sudden onset of pain. Their range of motion at 24 h is typically significantly reduced with pain on walking. There is typically obvious and significant weakness in contraction (1).

Grades 3a and 3b can be differentiated by the location as stated above. 3a typically extending to the periphery of the muscle. Whereas 3b being within the muscle/at the musculo-tendinous junction (1).

Grade 4:

Grade 4 injuries are complete tears to either the muscle (grade 4) or tendon (grade 4c). The athlete will experience sudden onset pain and significant and immediate limitation to activity. It is possible that a palpable gap over the muscle injury be felt (1).

Need an assessment or treatment following an acute muscle injury?

Call 9873 2770 or book online with one of our Physiotherapists today.

Reference:

Pollock, N. et al. (2014) “British athletics muscle injury classification: A new grading system,” British Journal of Sports Medicine, 48(18), pp. 1347–1351. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2013-093302.